Muhammad Ali was buried today in his hometown of Louisville, Kentucky. The Mayor reported that about 100,000 people lined the streets to view the nineteen-mile long procession. Millions of people watched the event for over eight hours on television. The funeral procession, which was held in a Louisville civic center was attended by over 20,000 ordinary citizens, politicians, athletes, artists, friends, and family member. Ali will be remembered for many distinguished accomplishments. He won the Olympic Gold Medal for boxing in 1960 at age 20. After returning home, he reportedly threw his medal in the river because the waiters would not serve him at the segregated all-white lunch counter. In 1964, he defeated Sonny Liston to become the heavyweight boxing champion. Afterward, he joined the Nation of Islam, changed his name from Cassius Clay to Ali, refused to serve in the Army over religious objections, was charged by the U.S. Government with draft evasion, sentenced to a jail term, stripped by the boxing commission of his title, won a Supreme Court decision to have his jail sentence overturned, re-captured the boxing title three times against l boxing notables Joe Frazier and George Foreman, regained his reputation and fame, retired from boxing in 1981, and became an ambassador to the world for the rest of his life. Throughout his career, Ali wanted to be called, “The Greatest.” In the days leading to his funeral, reporters were quick to top each other in describing his superlatives: “He was kind to everyone; he never forgot his friends; he looked out for the common man; he was a great family man; he was a man of peace.” Religious officials from the Muslim, Jewish, and Christian faiths spoke at his memorial service. Ali requested this religious diversity to promote world peace. Some commentators proclaimed that just saying Ali was “The Greatest” wasn’t enough for a man who influenced the as many people throughout the world in as many ways as the Champion. It is then indisputable to say that Ali, in his lifetime, was among the most acclaimed personalities of the twentieth century. Besides his worldly achievement, he was notable for beginning a trend of using the media to bring attention to his celebrity status. Today, it is an accepted, and perhaps expected, that famous people use every trick to gain more attention.

In the days leading to his funeral, reporters were quick to top each other in describing his superlatives: “He was kind to everyone; he never forgot his friends; he looked out for the common man; he was a great family man; he was a man of peace.” Religious officials from the Muslim, Jewish, and Christian faiths spoke today at his memorial service. Ali requested this type of religious diversity to promote world peace. Some commentators proclaimed that just saying Ali was “The Greatest” wasn’t enough for a man who influenced so many people, in as many ways, as the Champion. It is indisputable to say that Ali, in his lifetime, was among the most acclaimed and important personalities of the twentieth century. Besides his worldly achievement, he was notable for beginning the trend of using the media to bring attention to his celebrity status. Today, it is an accepted, and perhaps expected practice, that famous people will use every trick possible to gain more fame and Likes on social media. It is hard for us to remember a time when modesty was considered the most admirable virtue.

Last weekend, during a trip to Massachusetts to celebrate my birthday with my daughter and wife, I heard the news that Ali died. The reports were more memorable to me because “The Champ” died on June 3, which is also the same date my birthday. In Litchatte last week, I wrote that Bobbie Gentry’s song, “Ode to Billie Joe,” opens with the line, “It was the third of June, another sleepy, dusty Delta day.”Even though Billie Joe (a fictional character) and Muhammed Ali lost their lives on June 3, I had a happy celebration last Friday at my daughter, Tara’s house, in Greenfield Massachusetts. It was followed by a Saturday of hiking and visiting the “Bridge of Flowers.” We were planning to spend Sunday at outdoor events but woke up to find that rain had started and was predicted to for all day. Consequently, we needed to find indoor entertainment. We started off by visiting a nearby butterfly museum. I asked Tara if we were anywhere near the Emily Dickinson Museum and, if so, could we possibly visit there? After looking it up, we found that it is in Amherst, Massachusetts and only about forty-five minutes away. What apparently sealed the deal for my family was that there is also an authentic Chinese Restaraunt in Amherst. So, after a tasty Asian lunch, we proceeded to the museum and signed up for the 90 minute guided tour of the house that Emily grew up in and wrote all of her 1800 poems. Although I knew something about Dickinson and had enjoyed her poetry for many years, I learned a great deal from the excellent museum tour. Few would be opposed to the idea that Dickinson was as important to poetry as Ali was to boxing. However, only her close friends and family realized that she wrote. Fewer than 12 of her poems were published in her lifetime and the majority of those were done so anonymously. The rest were discovered by her sister Lavinia in her room and other locations of her sprawling house after she died in 1861. Over-edited versions of her poetry were published and became “best sellers” within three years after her death. However, complete versions, faithful to her original manuscripts, were not available until 1955, when the scholar, Thomas H. Johnson, published The Poems of Emily Dickinson. Below, see the earliest Daguerreotype of Emily Dickinson at about age 16.

Emily Dickinson was born in Amherst in 1830 and except for a few occasions where she traveled to Boston and Washington, she led her life as a recluse in her hometown. Although she attended the Amherst Academy for seven years and then briefly attended the Mount Holyoke Female Seminary, she seldom left the grounds of her home after she reached the age of twenty-five. Fortunately, she lived in a sprawling and luxurious house on eleven acres and was supported financially at first by her rich and famous political father and then later by her brother, Austin. Though she spent much of her time in her room, which is still preserved fully intact at the museum, she was also actively involved in gardening, baking, and interacting with the children in her town. She even encouraged them to play on her property. She had a few close friends and to several of those, she also sent poems for their comments. The most noted of these friends was Susan Gilbert, who also became the wife of Emily’s brother, Austin. However, Emily did not attempt to have her writing published in her lifetime. There were a variety of possible reasons for her reluctance. Women were not accepted as writers for much of the nineteenth century. Her views about spirituality were strongly in opposition to the leaders of the religious establishment. Her poems have a free-form and lyrical quality that express unique rhythms and convey themes of love, the soul, God, and the meanings of life and death. Perhaps, they are better understood by contemporary readers than they might have been if she had published them. Among Emily’s most interesting personality characteristics was her humility. In contrast to modern celebrities, she worked hard to ensure that she did not receive acclaim in her lifetime. It is unclear whether she considered that her works might one day be considered among the finest poetry ever written. The poem that she wrote in 1861, that starts off with, “I’m Nobody! Who are you?” also explains why she did not want to expose her poetry to public scrutiny during her lifetime:

I’m Nobody! Who are you?

Are you –Nobody—Too?

Then there’s a pair of us!

Don’t tell! they’d advertise—you know!

How dreary—to be—Somebody!

How public—like a Frog—

To tell one’s name—the livelong June—

To an admiring Bog!

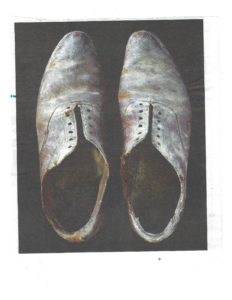

In the above poem, Emily speaks to us directly, saying that she is just like us. She warns that if we try to draw attention to ourselves, then it will be advertised in ways that we cannot control. By pointing to our accomplishments, she thinks that we will become the object of public scrutiny like “a frog” or a butterfly in a museum. She believed that she would have a “dreary life” and bring undue attention to herself if she published and read her her poetry “to an admiring Bog!” She considered that it was as useful to speak to frogs in bogs as it would be to defend her her poetry and reclusive lifestyle to critics who could not understand what she was trying to say or do. Her poem also warned nineteenth-century readers that there might an onslaught of publicity-seeking artists who followed her. She died in 1886 and had previously asked to be buried in a white coffin and dressed in a white robe (symbolizing purity). She had also asked several Amherst College professors and household workers to be pallbearers of her coffin on the condition that their names not be disclosed. Those pallbearers and a few friends and family members are the only ones who attended her quiet funeral. Emily Dickinson’s life and passing could not be more different than Muhammed Ali’s. This column seeks to bring greater attention to the humble lifestyles of Dickinson more than to detract from the accomplishments of Ali. I consider both of them to be among The Greatest Americans who ever lived! Emily Dickinson was also a champion who fought against the prevalent social and religious prejudices of her lifetime. Also, Ali wrote some very interesting poetry: Remember his anthem, ” I am going to float like a butterfly and sting like a bee!” I think that even Emily would have liked that line. I believe that she would have also appreciated Ali’s efforts to bring attention to the civil rights cause which proclaimed that black people are not—Nobody!

##############################

Murray Ellison received a Master’s in Education at Temple University (1973), a Master’s of Arts in English Literature at VCU (2015), and a Doctorate in Education at Virginia Tech in 1987. He is married and has three adult employed daughters. He retired as the Virginia Director of Community Corrections for the Department of Correctional Education in 2009. Currently, he serves as a literature teacher, board member, and curriculum advisor for the Lifelong Learning Institute in Chesterfield, Virginia, and is the founder and chief editor of the literary blog, www.LitChatte.com. He is an editor for the “Correctional Education Magazine,” and editing a book of poetry written by an Indian mystic. He also serves as a board member, volunteer tour guide, poetry judge, and all-around helper at the Edgar Allan Poe Museum in Richmond Virginia. You can write to Murray by leaving a Comment or at ellisonms2@vcu.edu or by seeing him at the Poe Museum (see below):